One of my more enjoyable Ed TALKS happened recently when I brought Kim Jones, Marissa Fagan, and Alex DeDonker to the virtual table to talk about how they train their software teams on security. Below are some highlights, tips, and practical suggestions from those three pros.

Bring the “So What?”

Kim is a dynamic and excitable guy, but also fiercely practical, perhaps due to his military training, his New England roots, or both. He is adamant that first and foremost, you must remember WHY you’re training. If you’re going to mandate an hour of someone’s time, you need to have answers to common questions – and if you can’t provide them ahead of time, then don’t roll it out training:

- Why is this something I should know about?

- What can I apply immediately?

- How will this help me do my job better?

Marissa agreed, tying it back to the need to meet developers where they live. It’s important to have the end goal in mind, plan your program to achieve desired outcomes, and sequence them properly. Don’t just throw things against the wall and see what sticks. Interview your audience to understand their goals and how training can help. That way, they pull the training as it fits into their personal development goals or increasing velocity goals (a common one for software teams.)

Measure… anything!

In the absence of industry metrics, we need to baseline goals, completion percentages, or other key performance indicators – this is critical to reach achievable goals along the way and compare relative progress.

Melissa at Atlassian said that even subjective measurement has proven useful in her experience. Don’t overlook simple surveys, as they still have utility. Doing a short sort of net promoter score (NPS) question, asking your developers, “Did this provide a training you think might have applied to a bug you’ve seen in the recent past?” or something to that effect. The key is to tie it into on-the-job context and, ideally, right at the end of the training itself. If your vendor or your LMS doesn’t allow you to do a survey, then include it as part of the assessment at the end. But collect that feedback – in context and at the appropriate time, right when training is finished. Microsoft captures NPS-like scores for the training, too, and can see in the feedback that this is exactly what their teams want and what they’re missing in other training areas in terms of how they want to learn and engage.

Talk to me

Marisa echoed the importance of teams being connected and sharing what they learn – a co-ownership driving toward the success of the program goals. In the security department, they’ve got people that are outward-facing and people that are inward-facing. Teams that co-sponsor a piece of each other’s mission to have that accountability create a better brain trust to solve these problems. Each team has information that other teams don’t have on each of the subjects. Her team is responsible for security awareness, but they also run a human risk program that does phishing and other kinds of human-related testing. They work closely with the Atlassian intelligence team to create a back-and-forth relationship, where both teams test and report – in the process of sharing, both create a culture for their team members.

Marissa also recently delivered a very interesting talk at RSA Conference. She talked about security champions and belt programs. She feels that because training vendors have improved and modernized their approaches, these dynamic, hands-on, real-world “ripped from the headlines” simulations are achievable now. The research to find the right vendor mix for your mission can be kind of time-consuming, she advised, but well worth it.

At Microsoft, alignment enables and drives communication. While the Education & Awareness teams are not particularly technical, they work closely with those teams that monitor situations and track SLAs and bugs. With data on hand, they can identify which teams need some hand-holding, whether it be more onboarding training in a specific area or whatever is holding them back to achieving green on Microsoft’s red-yellow-green status reports. A great example is their Azure security benchmark (ASB) program. Everyone needed to onboard their service through ASB, and The Education & Awareness team worked directly with the monitoring team to identify 50 people who had not onboarded to ASB. While the Education & Awareness team ultimately built out and conducted the training, the monitoring team in Azure identified the need for that training. Alex contests that if you have technical teams monitoring what’s going on in security, yet those teams are far removed from the team that is educating your employees, that’s probably a mistake.

For Intuit, this is where security champions come into play (more on that below), but it needs to be a 2-way street, which means a collaborative, open dialog with those who raised their hand to be a champion. It’s not just about setting expectations for them but also how you improve, edify, support, and help grow those champions. Instead of “Oh, you want to learn about security? Great – now you’re the security champion,” give the program form and function. Belt systems, just like in martial arts, can be used with software teams to identify those who develop particular skills and obtain mastery of those skills. For Kim, a senior belt on a software team (security champion) becomes his liaison, his interpreter, and the person who brings back information to the security team to say, “Hey, we really have a need for X, or I think I can do Y, or what do you think about experimenting with Z?” Then you get to grow that particular muscle exponentially versus linearly. He warned, though, that most developers are compensated for releasing software on time and under budget, and until that changes, they’ll view security as a tax that gets in the way of their job unless you get this 2-way communication right.

Build Security Awareness, Specialists, and Champions

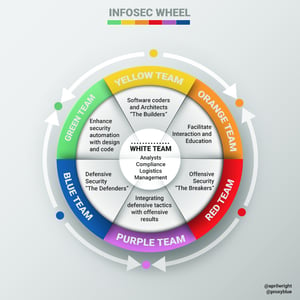

April Wright created the InfoSec Color Wheel that takes the primary colors of Red, Blue, and Yellow and blends them to create Orange, Green, and Purple – all in the context of cybersecurity training. Teaching builders (Yellow Team) some Red Team tactics turn them Orange, facilitating security interaction and education. Teach Blue Teams (the defenders) some Red Team tactics to make them Purple. She also sees this as a continuum, with mixed colors and security champions that emerge in each group.

April Wright created the InfoSec Color Wheel that takes the primary colors of Red, Blue, and Yellow and blends them to create Orange, Green, and Purple – all in the context of cybersecurity training. Teaching builders (Yellow Team) some Red Team tactics turn them Orange, facilitating security interaction and education. Teach Blue Teams (the defenders) some Red Team tactics to make them Purple. She also sees this as a continuum, with mixed colors and security champions that emerge in each group.

There’s a related Gartner report titled 3 Steps to Integrate Security into DevOps, where they talk about the importance of belt systems and blended learning. Essentially, they recommend tiers of training that combine online or classroom education with a high fidelity, hands-on environment. This is important as learners need to be motivated (belts) and reached (blended learning) in a variety of ways.

The need for general and specialized skills is clear in almost every profession. I’m a mechanical engineer by trade, and all engineering majors need to learn core principles for non-mechanical disciplines, e.g., electric engineering basics, essential chemical engineering, etc. I remember going through all sorts of material science and aerodynamic engineering courses that helped when I was designing parachutes that would drop cargo from planes. I had to understand all the mechanical forces of my parachute system, but also the materials I chose, the wind & temperature effects at various locations, etc. The same should be true with software engineering. Each team member needs to understand core principles like trust no input, defense-in-depth, and so on. This ensures security is considered regardless of role and provides that common vernacular needed to solve problems. Then technology- and job-specific training is needed. Training an embedded systems software engineer on SQL injection or OWASP Web Top 10 Threats makes little sense; however, training that same engineer on how to constrain user input in C to avoid buffer overflows is both contextual and useful to their job.

Harkening back to a theme I touched upon earlier, I asked Kim Jones about something I heard from a client the week prior: “We train in silos, so we deliver in silos.” He agreed but felt the relationship was inverted – that because we build and deliver software separately, we tend to train separately. He explained with a relatable example as a cavalry scout where his commander took seriously that they were all cavalry soldiers first and individual specialties supported the mission.

Microsoft’s approach is a little looser, according to Alex. His team offers virtual badges and incentives – things people can brag about and post on LinkedIn. He talked of the example where Microsoft partners with Security Innovation to offer a variety of CTFs tournaments. He thinks it’s their best approach to hands-on learning amidst these trying pandemic times. We create private channels for roughly 80 to 100 players, and they’re grouped via Microsoft Teams. It’s an opportunity (often their first) to work with different people across the company and get the hands-on support to learn something – and everyone’s on camera. It’s their team for the tournament. There’s a Security Innovation person on just about every team, helping them get through the CTF challenges. This is really that security champions program at the smallest level – deployed specifically for the task of helping the team on their CTF. They want to have some fun and try it out and do it on their own. Microsoft engineers want to be part of something, as opposed to just watching a screen.

Watch the original Ed TALKS

Watch this Ed TALKS to hear how three professionals have up-leveled skills at Intuit, Microsoft, and Atlassian and gain insight from benchmark data from Security Innovation’s own expansive user base.

Watch Security Upskilling Software Teams: Insights from Microsoft, Atlassian & Intuit